Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

Program to an Interface, Not an Implementation (GOF 18)

By interface, we mean either an interface like in C# or Java or an abstract class. (See **Abstract Classes vs Interfaces ** )

Abstractions should not depend on details. Details should depend upon abstractions. The DIP tells us that the most flexible systems are those in which source code dependencies refer only to abstractions, not concretions. (2017 Martin 87)

Every change to an interface corresponds to a change to its concrete implementation. Conversely, changes to concrete implementations do not always, or even usually, require changes to the interfaces that they implement. Therefore, interfaces are less volatile than implementations. (2017 Martin 88)

We should prefer dependencies on pure abstract classes (or interfaces) and avoid dependencies on concrete classes. Any line of code that uses the new keyword violates the DIP. Sometimes violation of the DIP is mostly harmless. The more likely a concrete class is to change, the more likely depending on it will lead to trouble. But if the concrete class is not volatile, then depending on it is not worrisome. (2002 Martin 269) (See Stable vs Volatile Dependencies.)

The String class, for example, is very stable. Changes to that class are very rare and tightly controlled. We do not have to worry about frequent and capricious changes toString.

Interfaces describe what it can do, whereas classes describe how it is done. Only classes involve the implementation details—interfaces are completely unaware of how something is accomplished. Because only classes have constructors, constructors are an implementation detail. An interesting corollary to this is that, aside from a few exceptions, you can consider an appearance of the new keyword to be a code smell. (McLean Hall, 83) (See Using the new keyword.)

Presumably, it is OK to refer to concrete classes in the entry point of the application. This is usually the Main function the system invokes when the application is first started.

The DIP is the fundamental low-level mechanism behind many of the benefits claimed for OOD.

The DIP is the hallmark of good OOD; if we do not invert the dependencies, it is a procedural design.

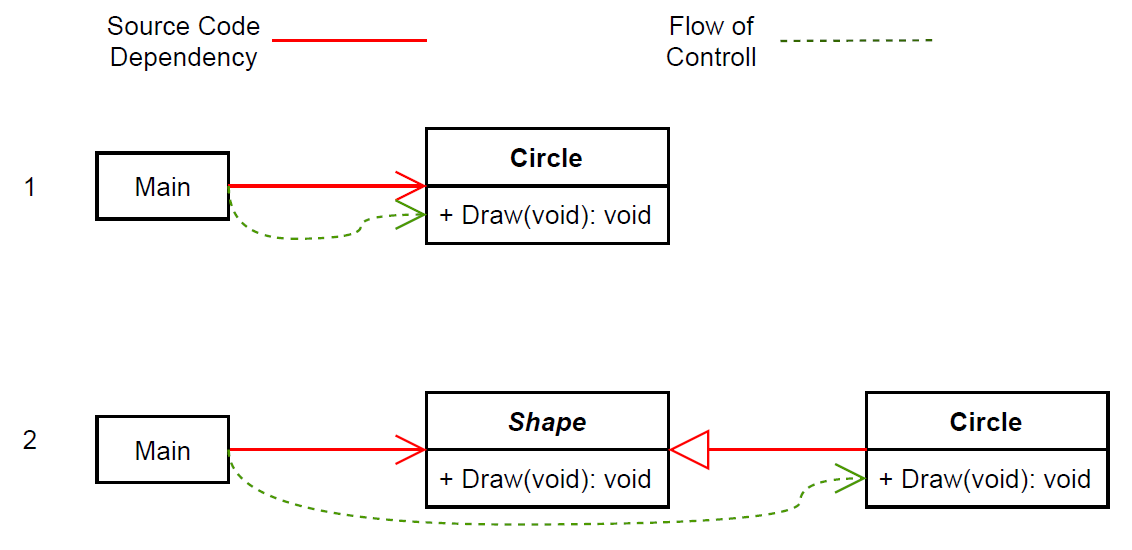

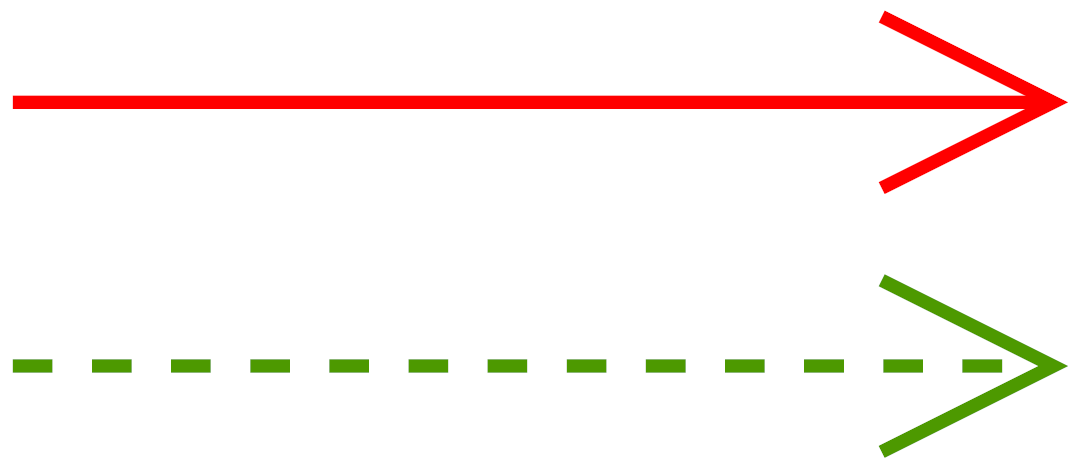

The dashed lines represent the flow of control. Notice that in the first diagram, Main calls the Draw method of Circle. In order for Main to call Draw, it must somehow mention Circle as a source code dependency, which is depicted using the dashed lines. In C it is accomplished with #include, in Java with an import statement, and in C# with a using statement.

Notice that in the first diagram the dependency arrow and the flow of control arrow point in the same direction, which is not an example of SOLID object-oriented design.

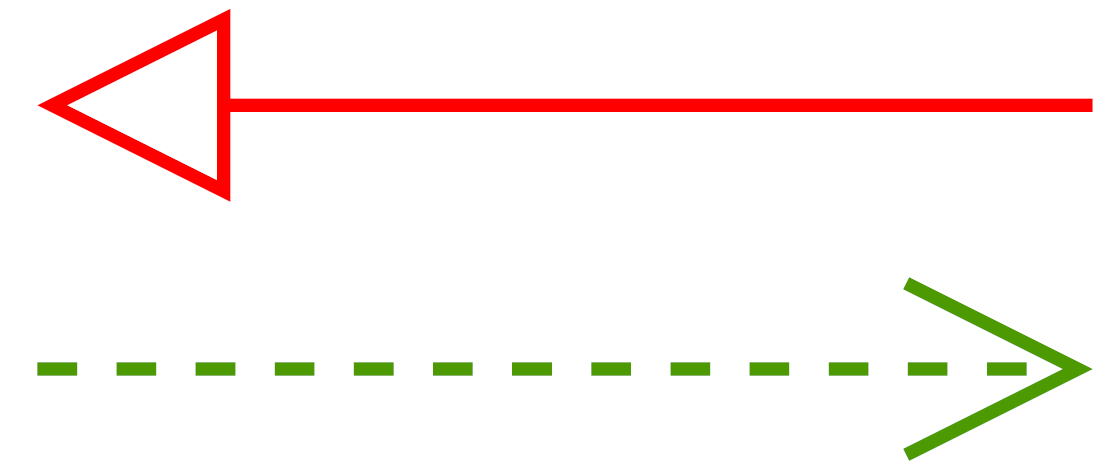

With polymorphism, something very different can happen. In the second diagram, Main calls Draw through the Shape interface. Observe that the source code dependency (the inheritance arrow) points in the opposite direction compared to the flow of control. This is why it’s called dependency inversion. (2017 Martin 45)

In the second diagram, Main is calling the Draw method of Circle and is not calling the Draw method on Shape because there is no such thing as a Shape object (Shape is an abstract class). Therefore, it is a circle, or a square, or a triangle masquerading as a shape. (Riel 95)

See Also:

Avoiding Liskov Substitution Principal Violations in Type Hierarchies

How do we write a test for a private method (mentions DIP via interfaces)

Relationship between Dependency Inversion, Dependency Injection, Inversion of Control and SOLID