Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

SubTypes must be substitutable for their base types.*

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP) depends on abstraction and polymorphism. In statically typed languages such as **C# **, polymorphism is achieved through inheritance, where classes implement contracts defined by base classes. The Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) provides guidelines for designing robust class hierarchies by identifying characteristics that maintain compliance with the OCP and common pitfalls that violate it (Martin, 2002, p. 111).

The LSP is one of the prime enablers of the Open Closed Principle (OCP). (2002 Martin 125)

Methods that consume Abstractions must be able to use any class derived from that Abstraction without noticing the difference. We must be able to substitute the Abstraction for an arbitrary implementation without changing the correctness of the system. Failing to adhere to the Liskov Substitution Principle makes applications fragile, because it disallows replacing Dependencies, and doing so might cause a consumer to break. (Seemann 241)

Inheritance with polymorphism and dynamic binding offers a powerful mechanism for developing reusable and extendable software. However, an overriding method can change or even redefine the overridden method's semantics and affect the superclasses existing clients. It can be dangerous if an overriding method in a subclass breaks the superclass's underlying assumptions or constraints. (Dianxiang Xu 121)

Inheritance Motivations & When LSP Bites

Inheritance is usually for:

Polymorphism – let clients treat many concrete types via one abstraction.

Implementation reuse – share code; no substitution intended.

LSP matters only when substitution can happen.

If reuse is the sole aim, prefer composition (or mark the class sealed/internal) to prevent future up-casts from turning a hidden LSP breach into a bug.

Unity’s MonoBehaviour

Unity scripts inherit MonoBehaviour chiefly for engine callbacks and editor support—code reuse. They are rarely handled as generic MonoBehaviour; GameObjects instead compose behavior by attaching specific components. LSP issues are therefore uncommon, but reappear if you up-cast ( e.g., GetComponents<MonoBehaviour>()).

Violations of the LSP

One of the symptoms of violating the LSP is needing to perform explicit case analysis.

This explicit case analysis violates the LSP because it relies on the specific subtype at runtime, rather than using polymorphism to handle different Shape implementations.

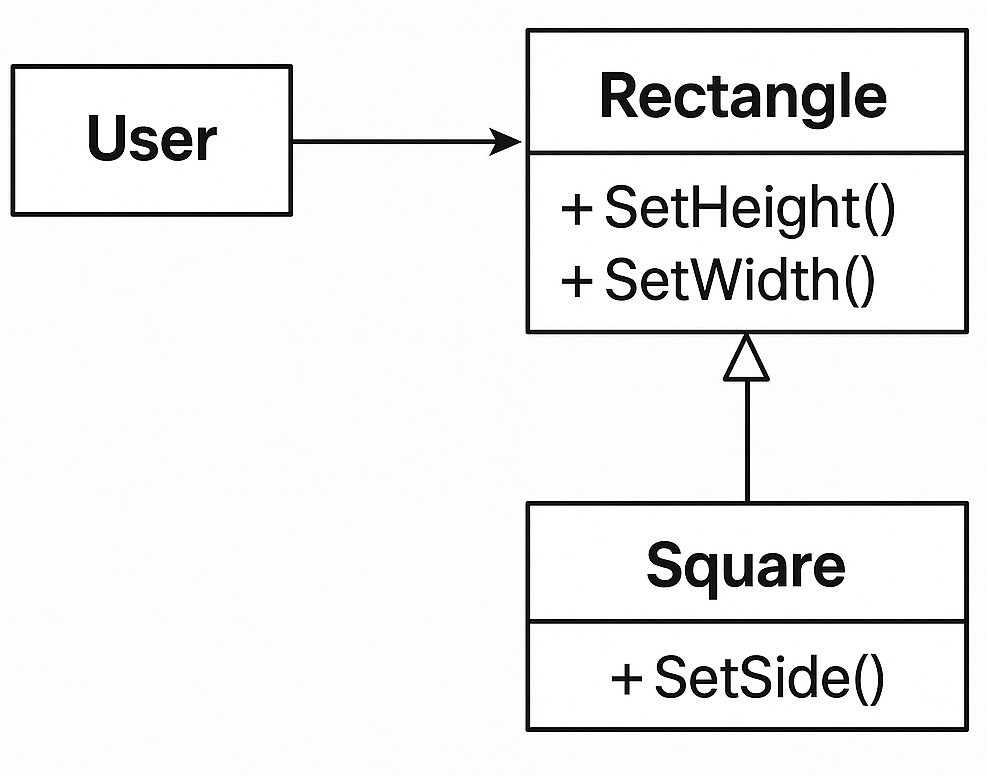

The Square/Rectangle Problem

Square is not a proper subtype of Rectangle because the height and width of the Rectangle are independently mutable; in contrast, the height and width of the Square must change together. Since the user believes it is communicating with a Rectangle, it could easily get confusing.

Stack vs. List: Design Considerations to Avoid LSP Violations

We know a Stack is something that has LIFO (Last In, First Out) behavior. We express this behavior in a Stack's public interface with Push(), Pop(), and Peek().

We know a List is something that allows us to add and remove items at arbitrary positions, using methods like Add(pos, item) and Remove(pos, item).

Implementing a Stack by inheriting from a List will cause the public interface of the Stack to include the public interface of the List. This makes the Stack class not cohesive because the inherited methods are incompatible with the LIFO behavior of Stack objects. (Dianxiang Xu 87)

The composition solution is for Stack to contain a List as a private member and implement Push(), Pop(), etc., by delegating the behavior to the List member.

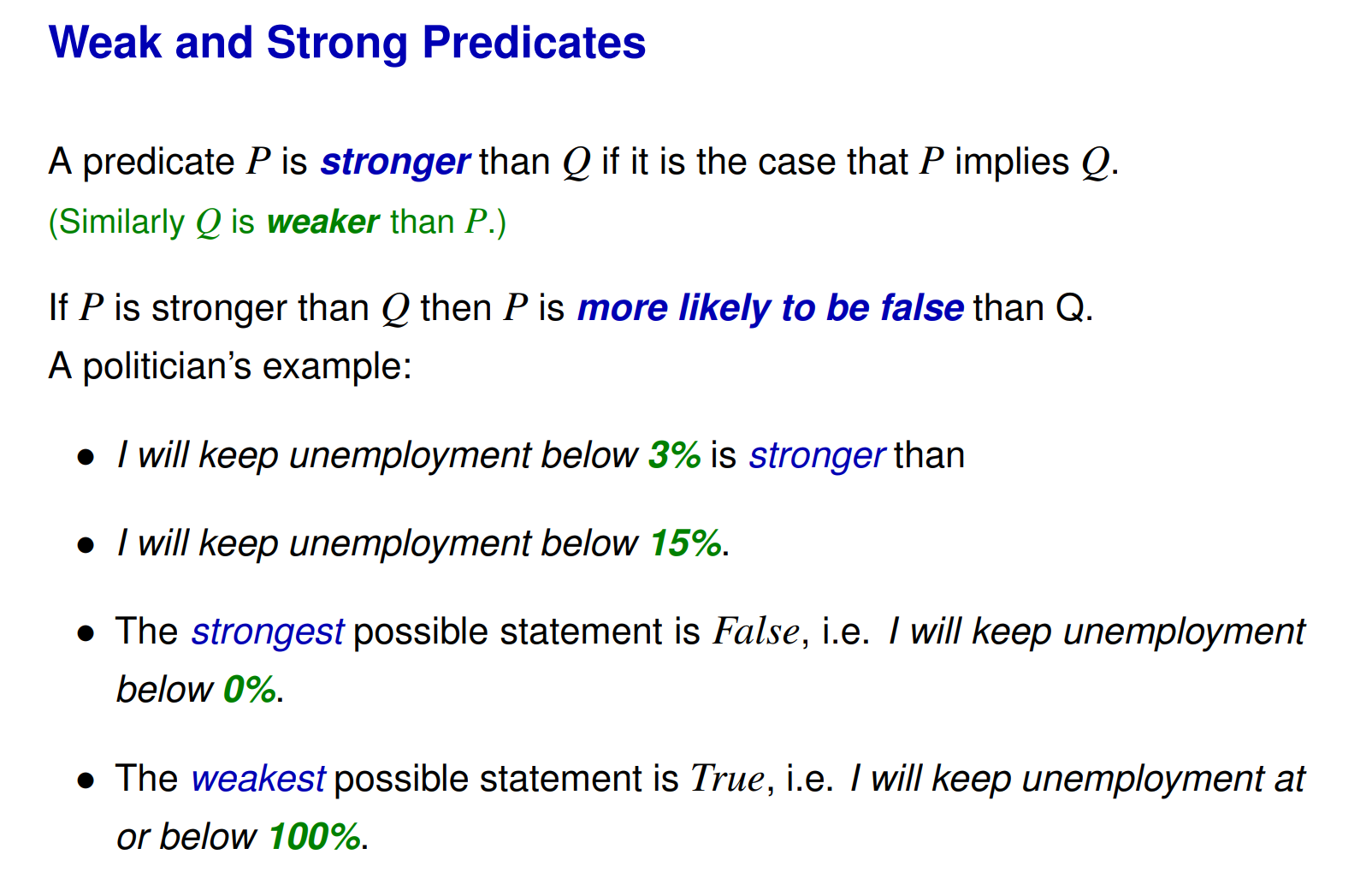

(Optional) Overriding Methods Precondition and Postconditions

An overriding method with a weaker precondition causes no harm to a client call that satisfies the original precondition before the call.

An overriding method with a stronger postcondition causes no harm to a client call that relies on the original postcondition being satisfied after the call.

https://cs.anu.edu.au/courses/comp2600/Lectures/17HoareII.pdf

*What is wanted here is something like the following substitution property: If for each object o1 of type S there is an object o2 of type T such that for all programs P defined in terms of T, the behavior of P is unchanged when o1 is substituted for o2 then S is a subtype of T. (Liskov)

See Also:

Avoiding Liskov Substitution Principal Violations in Type Hierarchies ( detailed example)

Explicit case analysis (switch/if-else statement) (LSP violation symptom)

Prefer Composition over Class Inheritance (Stack/List example)