Finding Test Cases

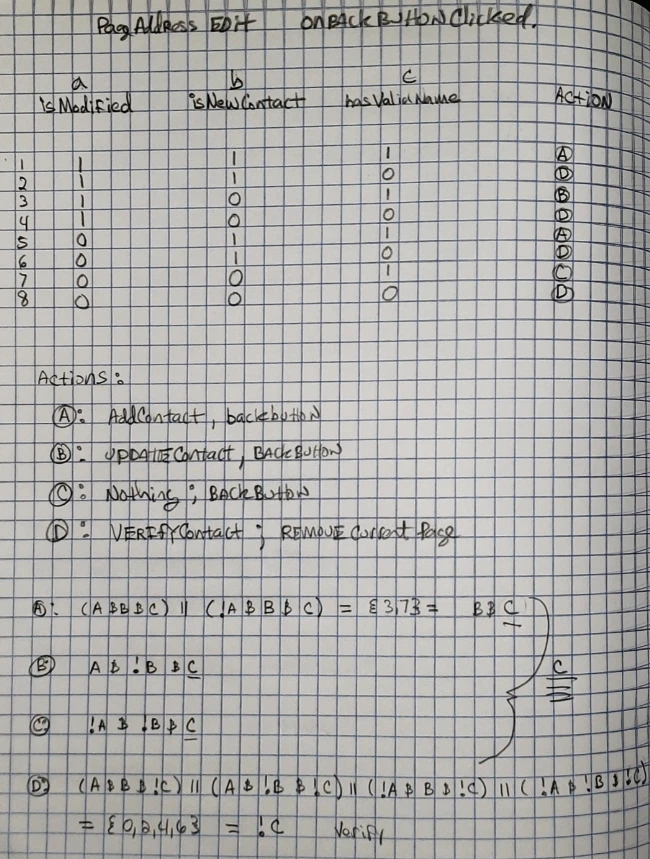

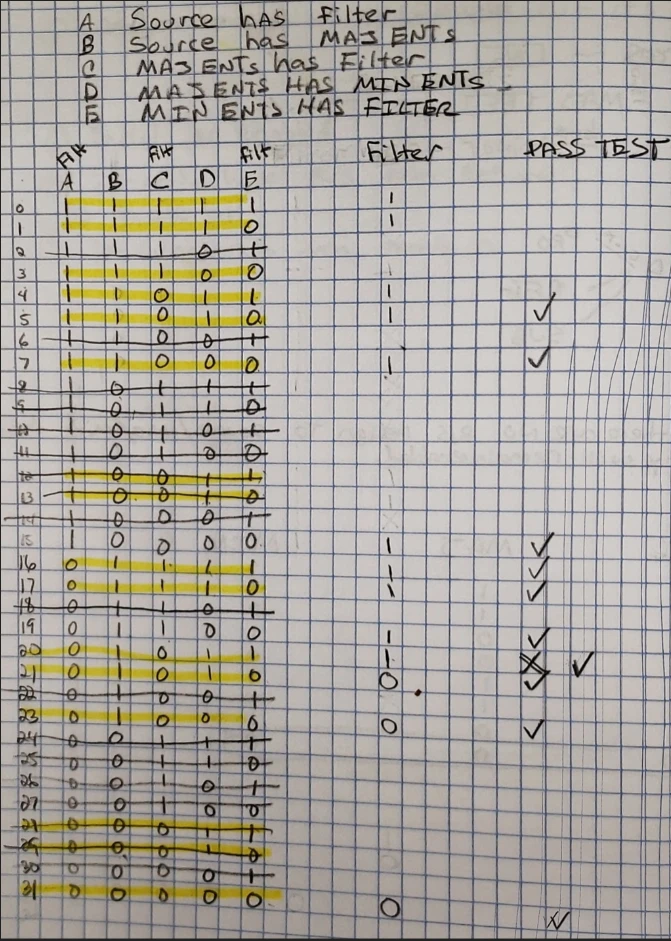

The following is the process and tools I used to create test cases. For simple methods, I sketch a truth table of the inputs, then analyze each row and write the expected result. I cross out any rows that are impossible or I don't care about. Finally, I create a test case for each relevant row on the table.

static bool Branch(bool a, bool b)

{

var result = false;

if (a)

{

if (b)

{

result = true;

}

}

return result;

}

|

|

|---|

There are 4 rows in the truth table, but since when a is false, the value of b does not matter, so we only need 3 test cases.

The first test case: a = true and b = true gets 100% statement coverage.

But this is only 1/3 or 33% total branch or decision coverage.

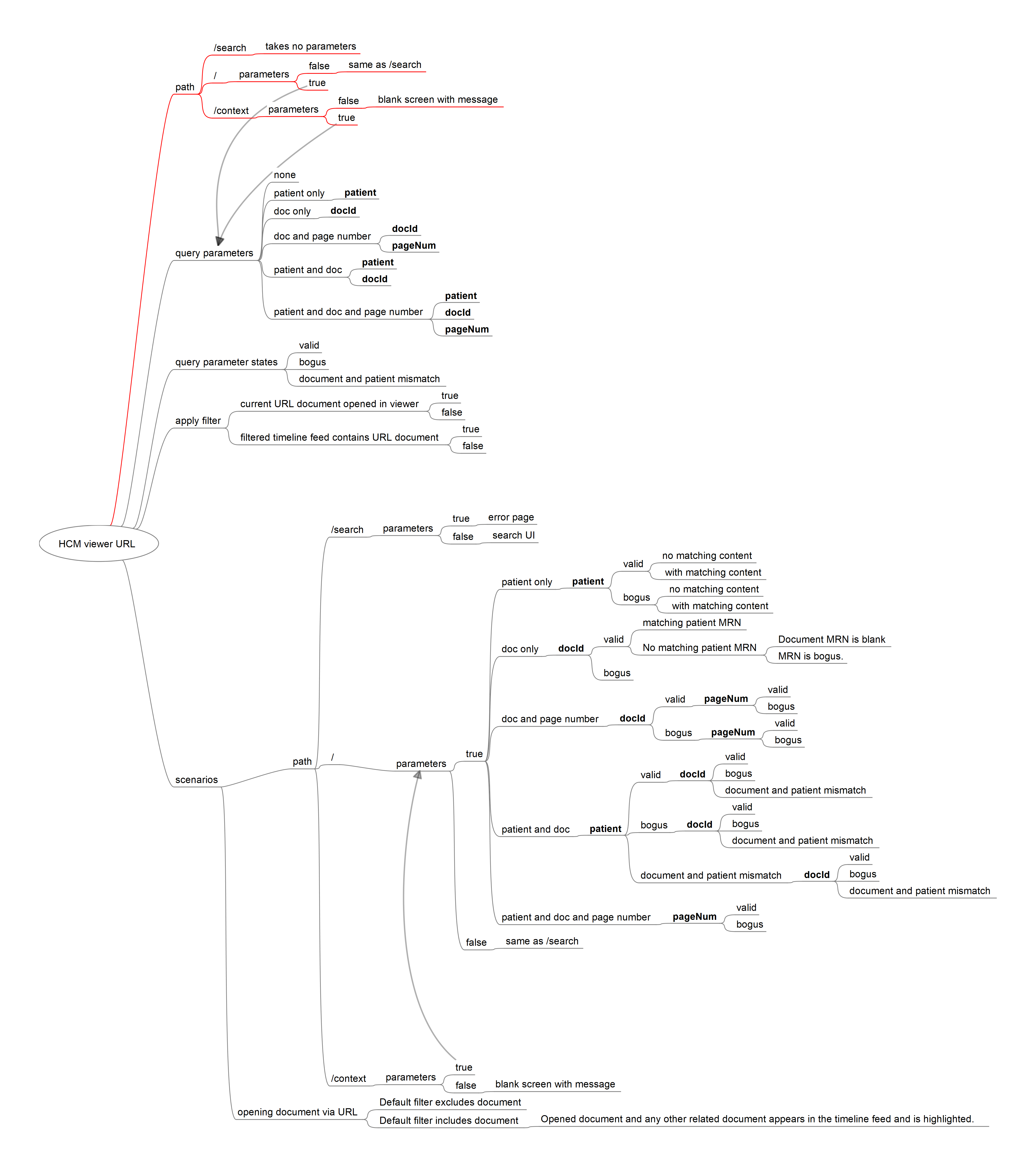

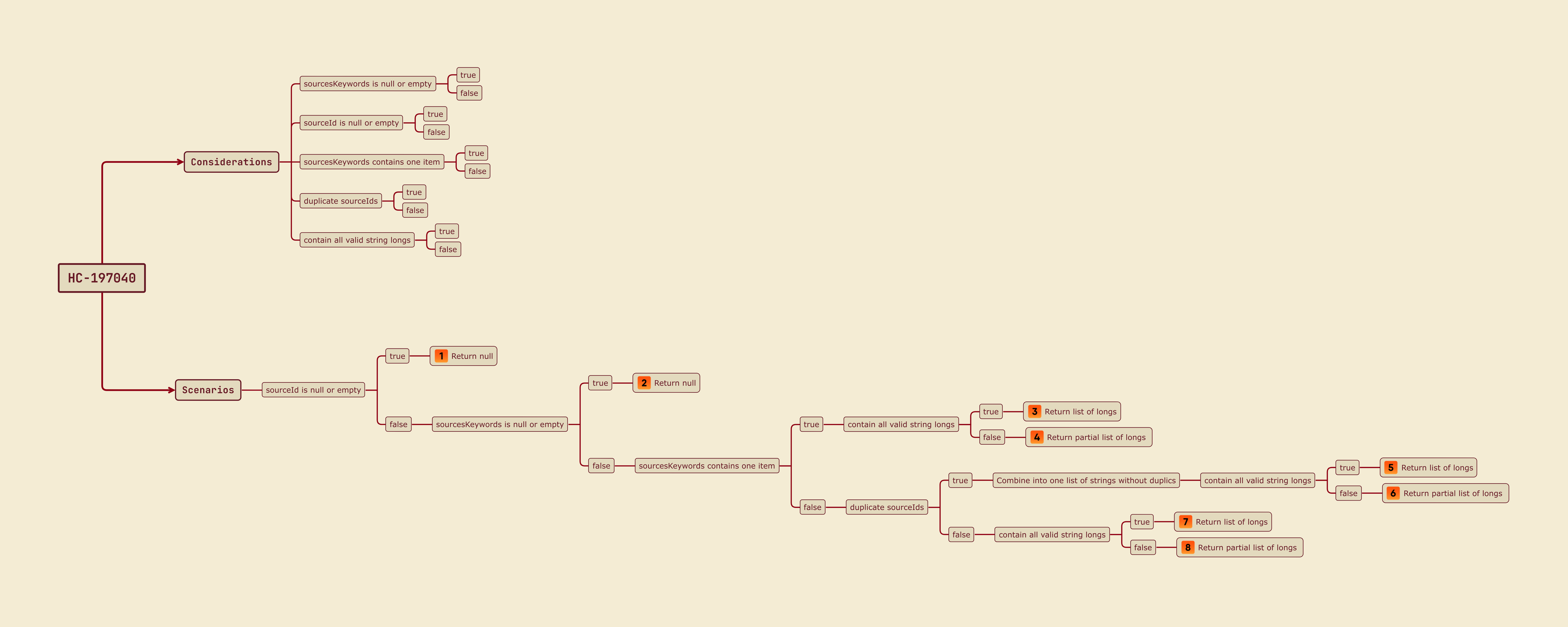

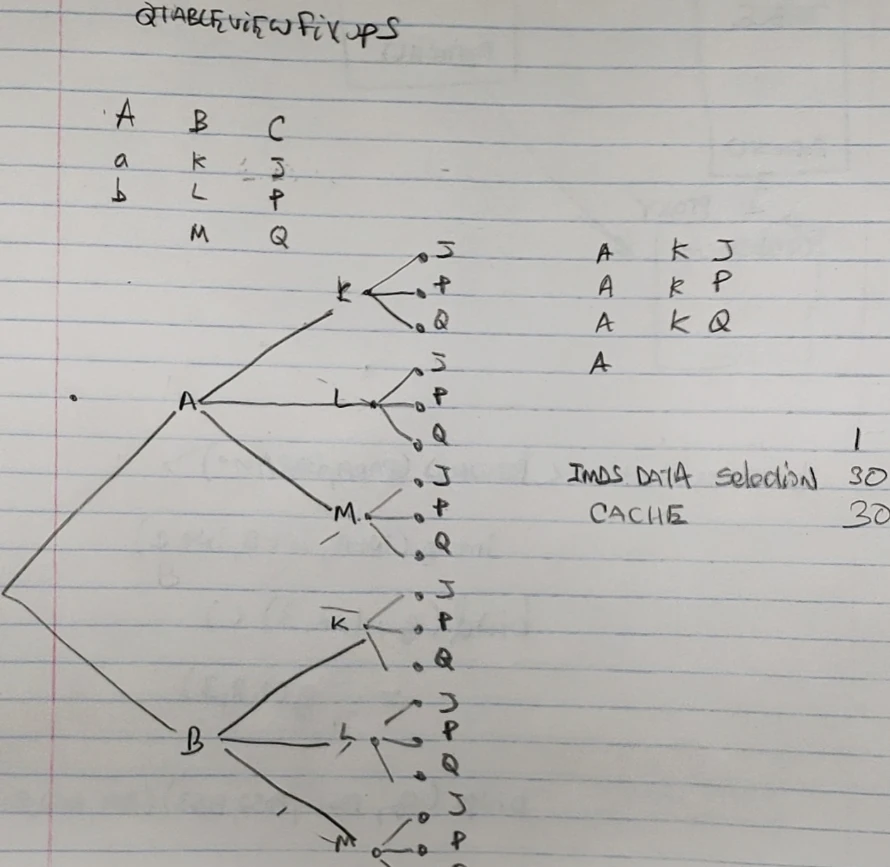

When things are more complicated beyond a couple of boolean values, I use a free mind mapping tool to help model the test cases and keep track of testing progress.

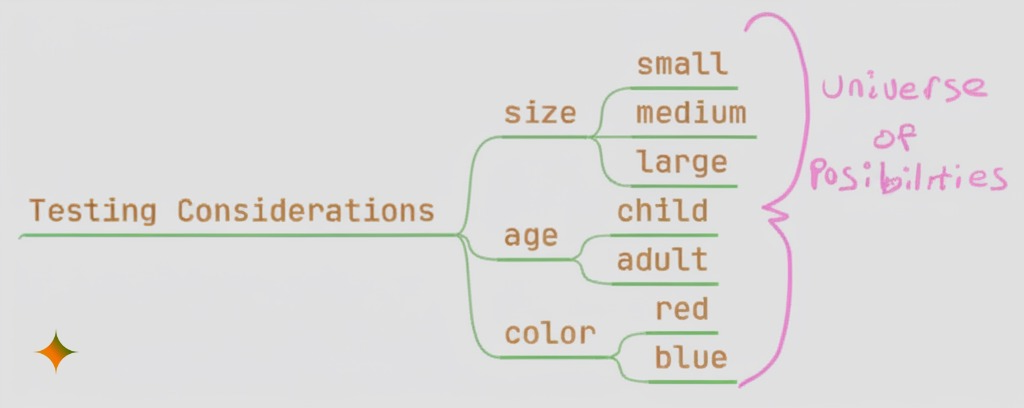

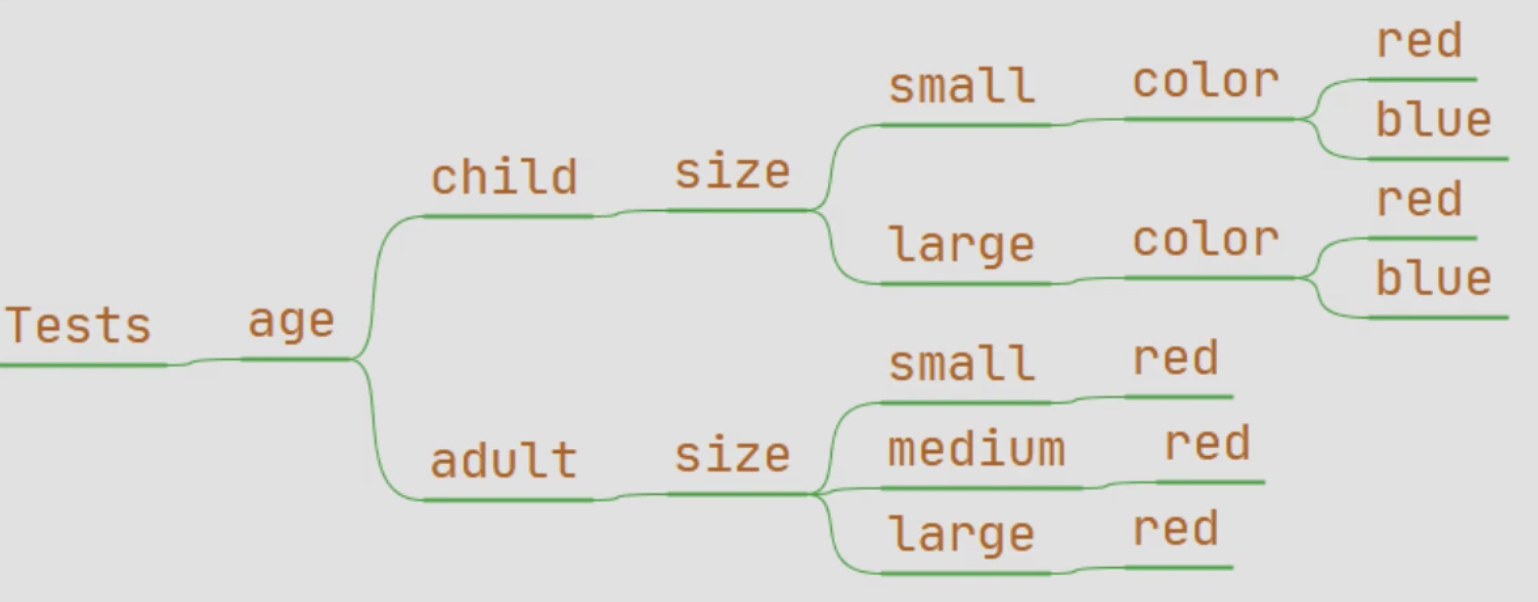

Let's say we're creating test cases around t-shirts that have 3 input variables: size, age, and color.

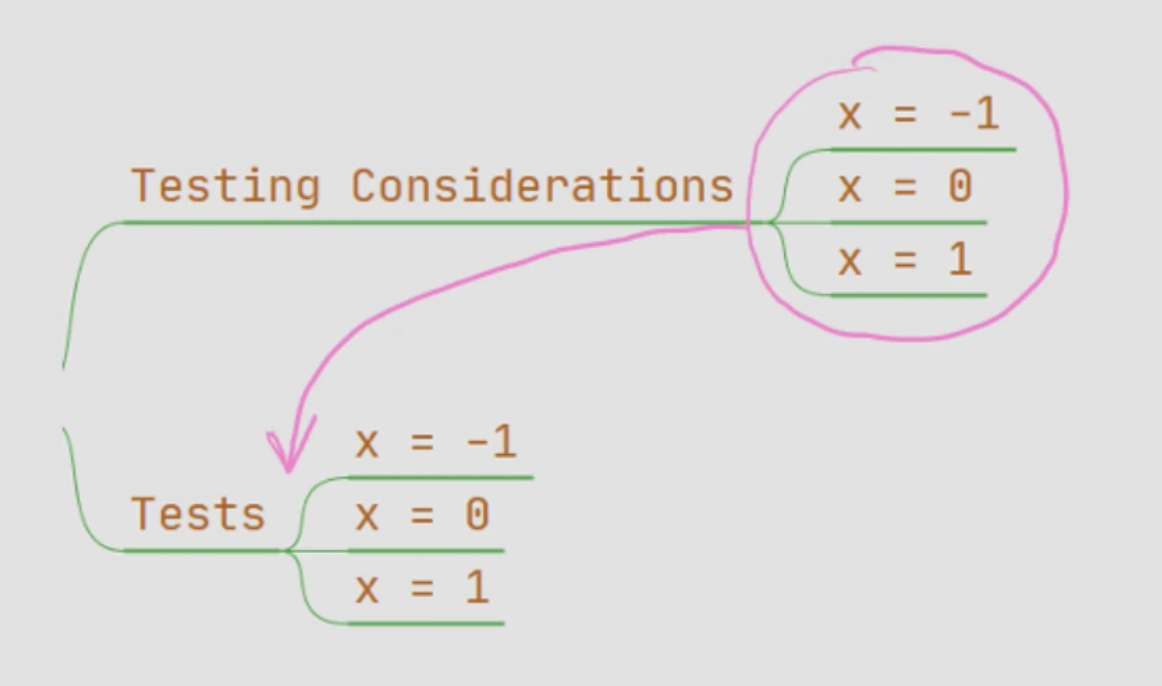

Create a node called Testing Considerations.

Append suitable values for each variable: size (small, medium, large), age (child, adult), and color ( red, blue).

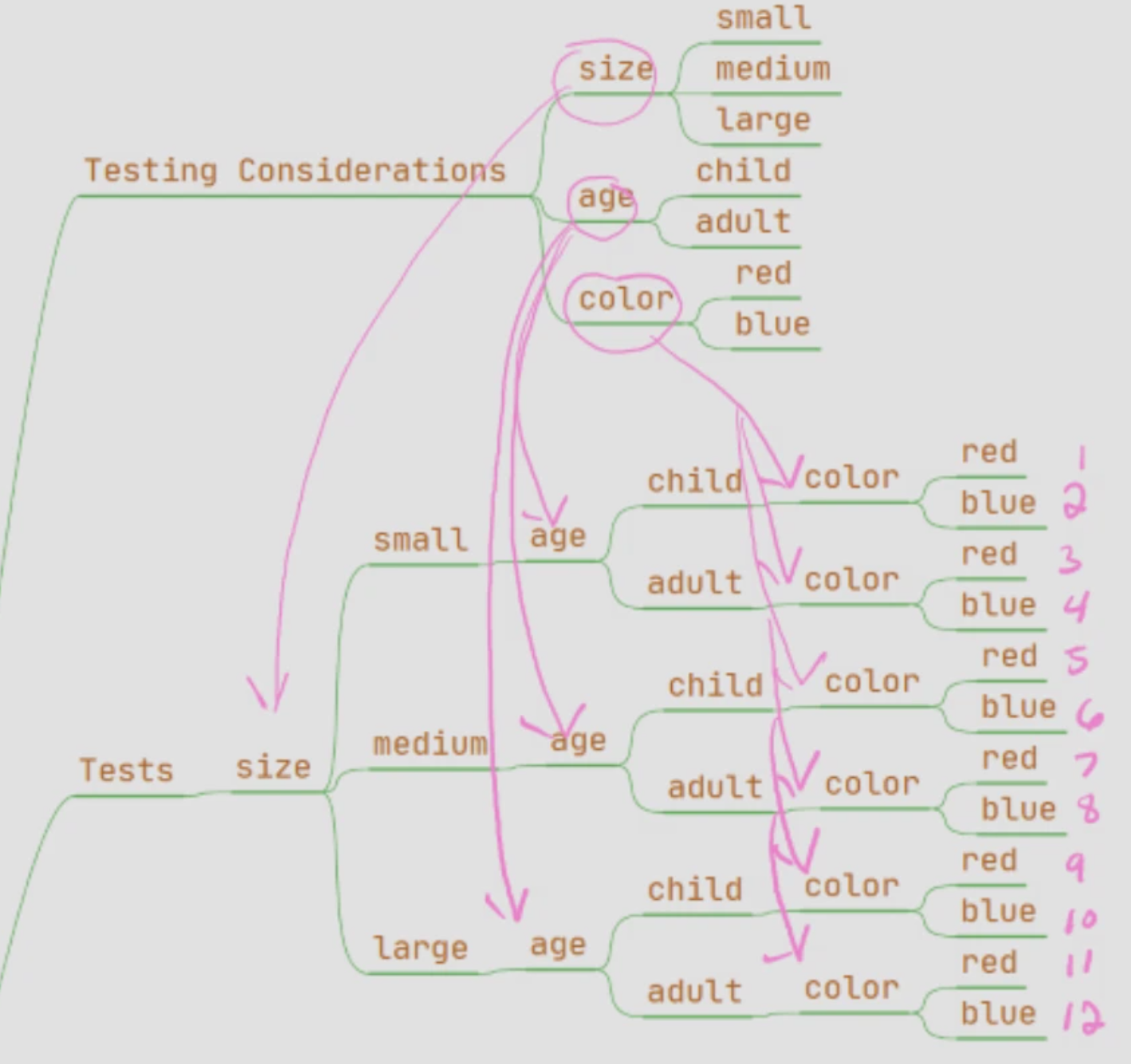

Create a node called Tests.

Copy and paste (append) the size branch to the Tests node.

Append the age branch to each size node.

Append the color branch to each age node.

The branch count equals the number of potential test cases.

3 size × 2 age × 2 color = 12.

Often there are constraints that allow us to prune the number of test cases.

Example constraints:

Child sizes only come in small and large.

Adult colors only come in red.

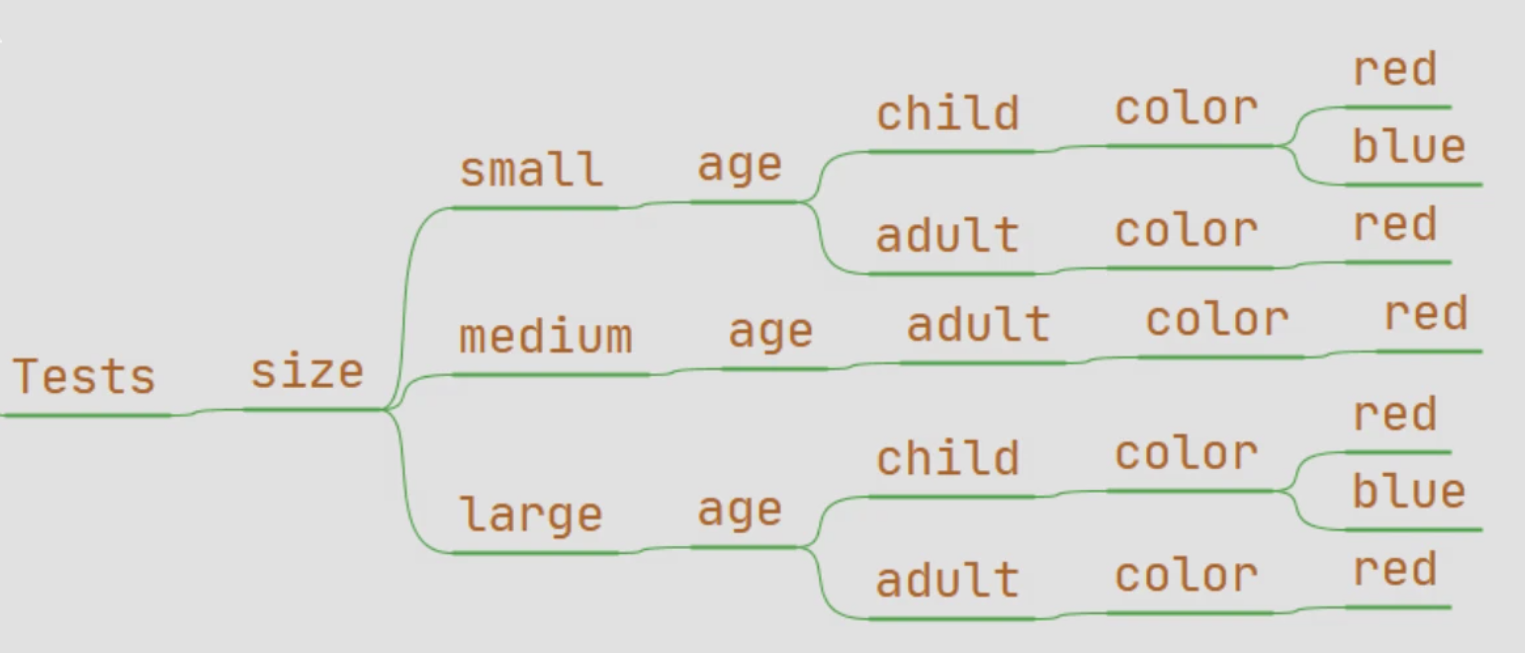

After pruning the tree, there are only 7 branches.

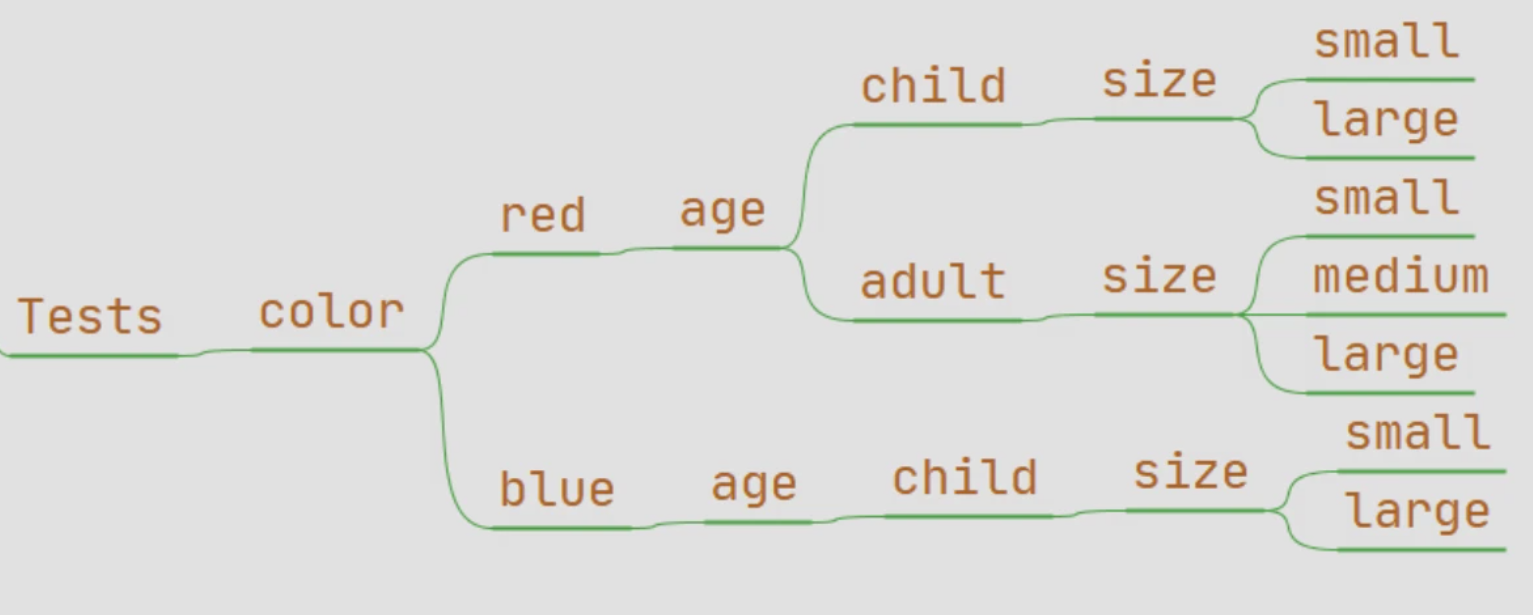

The order of implanting the nodes (size → age → color) is subjective and may need adjusting.

Therefore, I use a mind mapping tool since it allows you to easily modify the tree.

Shown here are three possible ways to create the Tests tree. The one you end up with depends on experience and ordering.

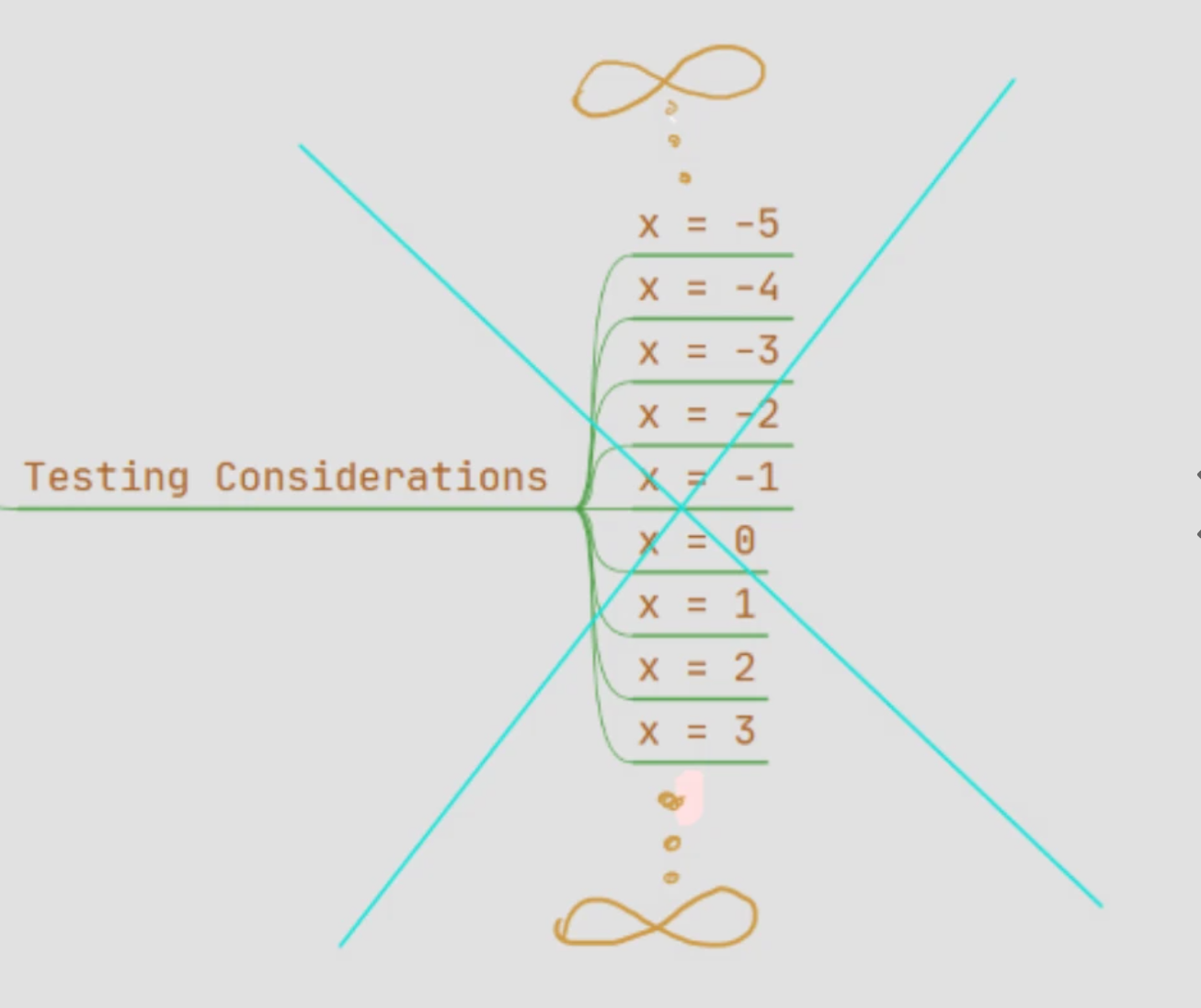

Equivalence Partitioning

Equivalence partitioning divides the input domain of a variable into groups, called equivalent classes, that represent interesting conditions. We expect two values of a variable belonging to the same equivalent class to produce the same test results (pass or fail).

An input variable has certain ranges of valid and invalid values. For example, an int variable for month ranges from 1 to 12, so any value less than 1 or greater than 12 is invalid.

For another example, say we want to compare two lists. There might only be 3 classes to consider:

All items in one list match the items in the other list.

Some items match.

None of the items match.

Equivalence partitioning can be subjective and application-dependent. Given an input variable, different people may produce distinct sets of valid and invalid classes for different applications. (Dianxiang 350)

When generating Testing Considerations, you don't need to include every possible value that an input variable can take. Use equivalence partitioning to generate a manageable subset of interesting values and be sure to include values for the happy path and the error path.

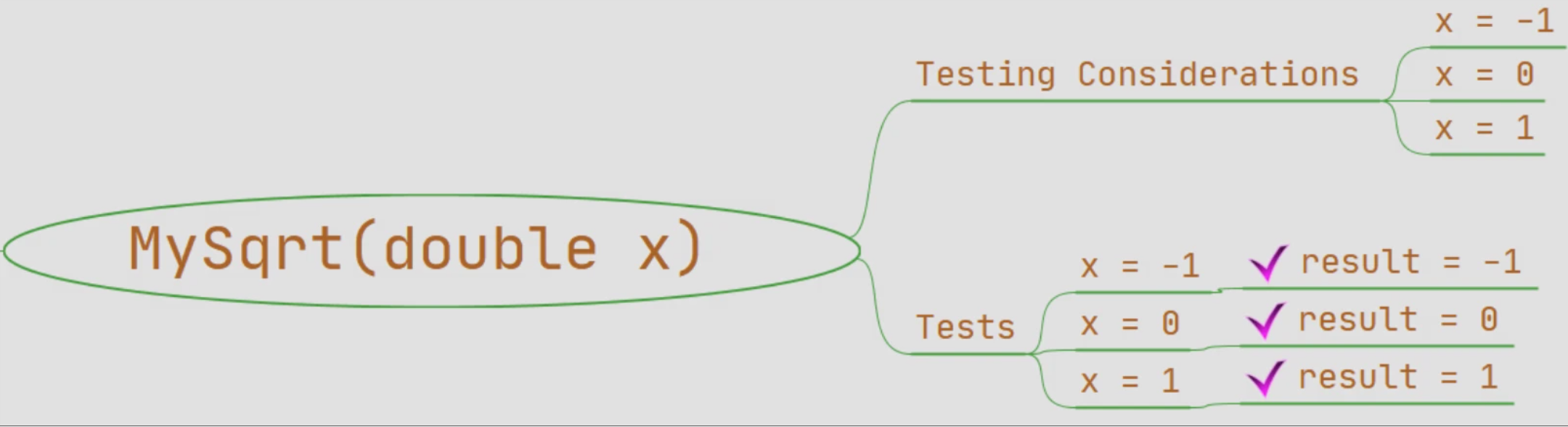

ExampleMySqrt() has an infinite (∞) number of input values but only about 3 interesting ones.

static double MySqrt(double x)

{

if (x < 0)

{

return -1;

}

return Math.Sqrt(x);

}

|   |

|---|

After I'm finished with creating the Testing Considerations and Tests branch, I add the result or expected value leaf to the end of each test branch.

At the end of each test branch, add a leaf that contains the expected test results.

As you add or run each test, mark each leaf to help keep track of your progress.

Real World Examples

Back in the Garmin Days

See Also: